Just after World War II and near the halfway mark of the 20th century, philosopher Gilbert Ryle published The Concept of Mind, a book widely credited with ending the philosophical division between physical and mental realms of reality. Continue reading “Gilbert Ryle, Reconnecting Mind and Body”

Tag: Heidigger

Positivism V. Nothing There, the Mind of a Frog

Wheeler. Jump! Clear. Jump, jump, jump – wheeler! Jump, splash. Jaws! Kick! Kick, kick.… Jump, jump, whee- Splat!

If you can understand that, then you and I have something in common. It’s all your misfortune and none of my own, because I have learned to live with it.

Among the best positivist thinkers today, Daniel Dennett stands out for clarity in his writing and for his willingness to follow the credo to its logical destination. I had been attracted to his work through a book titled The Mind’s I, which he edited with Douglas Hofstadter. It is a collection of essays, dialogues, and stories by various writers on consciousness and free will. Jorge Luis Borges splits his consciousness to write about himself in third person. Hofstadter tells how Achilles once spoke to a colony of ants – not to the individual ants, but rather to a colony of hundreds who spell out their answers by forming letter patterns on the ground. Richard Dawkins brings genes and memes to the feast. The editors made their selections well; the short, varied pieces are surprising, clever, thought-provoking, and entertaining. I’m sure you can find a used copy cheap. Later on I explored Dennett’s own focused presentation of the same topic in his book Consciousness Explained.

In the 1980s when I was working at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, an upcoming visit and evening seminar by Dennett was announced, open to the public courtesy of the University of Houston’s philosophy department. Neither my busy schedule as junior faculty nor the needs of a young family would deter me from going to the seminar.

I had never attended a lecture by an actual philosopher. There were courses in philosophy at Ole Miss, but the subject had seemed too outdated and quaint, hardly necessary as preparation for a scientific career. My plans barely changed even after a sophomore honors seminar in the classics taught, or rather led, by Ms. Anita Hutcherson, the most influential class I ever took. I did decide to minor in English and jumped into a creative writing course, not a small endeavor at Ole Miss.[1]

With a high sense of anticipation I drove across the city. The lecture itself provided more than I could have asked for, moving well beyond expectations and crystallizing a challenge that continues to provoke me today. Starting with a familiar foundation of biology and chemistry, Dennett built the case step by step for a philosophical proposal that the first- and second-person pronouns I, me, you, we, us will eventually fade out of human speech.

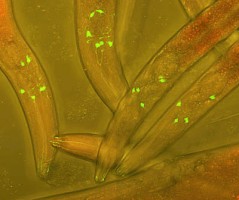

Dennett’s slides began with the simple, genetically mapped nervous system of the famous roundworm, Caenorhabditis elegans, and proceeded upwards phylogenetically. He showed the dissection of a frog brain and, as best I recall, said something like this: “Nobody knows what it’s like to be a frog. And do you know why that is so? The more we learn about the frog brain – the more we understand its centers for perception, integration, and response, we become persuaded of this conclusion: There is nothing there that explains ‘what it’s like to be a frog.’”

Dennett asked us to apply the same reasoning to human biology. The human brain is wondrously evolved to handle abstract ideas and complex reasoning, but fundamentally the neurologic substrate is the same as that of C. elegans or a frog. Science finds nothing in the brain to resemble a center of consciousness, nothing there to suggest a mechanism for free will, nothing there to evoke the sense of specialness that you may feel as a rational and emotional subject. After the last “nothing there,” Dennett pulled out his surprising prediction that the words I, me, you, we, us will gradually become meaningless and disappear from human speech…. if not in 75 years, then certainly in 1000 years.

I had been playing Frogger, a popular video game then. At the end of Dennett’s talk, I raised my hand and told him and everyone else what it is like to be a frog. Your consciousness while playing Frogger shrinks incredibly. You become completely attuned to avoiding the wheels of trucks on the road that can smash you flat or alligators in the stream whose huge jaws can pop you like a cherry tomato. You jump and think of nothing but wheels and jaws and the next jump, or your game will end.

Wheeler, jump! Clear. Jump, jump – river, splash.

Kick, kick, kick. Jaws! Squish. (Game over.)

That is how a frog thinks. Of course I figured it would be funny, but also intended to make a serious point. Everyone laughed and took it only as a joke. I had entered the brain of a frog in a video game, but they counted my experience as nothing.

When we as humans completely adopt the scientific viewpoint, according to Dennett, there will be no need for self-reference or reference to a particular other person. The words I, me, you, we, us testify to particularity and have no place in science. He can reasonably predict, therefore, that the personal pronouns eventually will pass from human speech, except in historical perspective.

Do you think that will come true? Or will the pronouns out-survive the prediction, which may fade away as a worn-out kind of selective nihilism typical of 20th century modernity?

Dennett’s best-selling book, “Consciousness Explained,” published in 1991, argues for a materialistic explanation of consciousness. Amid a voluminous display of psychological surprises and mind experiments, one finds this brief question with Dennett’s own answer:

Am I saying that we have absolutely no privileged access to our own conscious experience? No.[2]

Thus Dennett admits the experience of particularity.

Martin Heidegger called it dasein, which may translated roughly to be there. It testifies to my or your particular locus in the world. One might suggest that it means every person lives in his or her own skin, but it is not valid to say that “every person lives in his or her own skin.” Dasein means that I live in my own skin. I do not possess godlike oversight that informs me what everyone’s experience is.

Dennett was right! I do not know what it is like to be a frog. Neither do I know what it is like to be you. Unless you want to tell me.

Next post: Positivism VI. Less Than All

Previous post: Positivism IV. The Structure of Play

Searching for GSOT outline: Home

[1] Dr. Evans Harrington taught the creative writing course. Kind but firm in his criticism, he represented to me a crucial link between Faulkner and other Mississippi writers of the early 20th century and the current thriving literary community in the Oxford-Jackson-Memphis region.

[2] Dennett, D.C. Consciousness Explained. Little Brown, Boston, 1991, p.68.