On the first day of October 1962, James Meredith enrolled as the first black student at the University of Mississippi in Oxford – Ole Miss. He had been rebuffed 3 times earlier that year. This time he succeeded with the help of 400 Federal marshals and eventually 16,000 U.S. soldiers including units from the 101st Airborne Division.[1]

Meredith grew up on a farm northeast of Jackson surrounded by dense woods. His father “Cap” Meredith was the first in the family to own land. As recounted in a history about Ole Miss,

Cap instilled in his children a great sense of personal pride. No Meredith, including “J.H.” – the name “James” would come later in life – ever went inside a white person’s house because he or she would have had to enter through the back door. And Cap Meredith taught his children that this was dishonorable.[2]

In the days just before Meredith’s enrollment at Ole Miss, the segregationist governor of Mississippi, Ross Barnett, tried in vain to make several deals in telephone calls with Bobby Kennedy, the federal Attorney General. When he realized that Meredith must be enrolled, Barnett asked for a staged performance to demonstrate that he was submitting to overwhelming force. Again from the history:

“We got a big crowd here,” he explained to Kennedy, “and if one pulls his gun and we all turn, it would be very embarrassing. Isn’t it possible to have them all pull their guns?” Kennedy balked, but Barnett persisted: “They must all draw their guns. Then they should point their guns at us and then we could step aside.”[3]

Kennedy didn’t buy it, and Barnett stayed in Jackson throughout the events of the next few days.

A riot erupted at Ole Miss on the night of September 30, 1962, spreading into the town of Oxford by the next morning. The federal marshals stood in a ring around the Lyceum (pictured above), the main administration building which had once served as a hospital in the Civil War. This link provides a contemporary news report. White students from Ole Miss and other universities were joined by numerous outside persons, some heeding a call from resigned U.S. Major General Edwin Walker of Texas to join him there, forming a belligerent crowd that peaked around 2500. A driver-less bulldozer was twice launched against the marshals, but ran into large trees both times. The Lyceum building gained several bullet marks. A sniper killed a French reporter with a shot between his shoulder blades, and a jukebox repairman died from another bullet.

As federal troops poured in through the night and tear gas grenades had their effect, the rioters were pushed back from the campus. Two hundred, including Walker, were arrested.[4] The town square in Oxford was cleared the next day. Meredith enrolled at Ole Miss that morning and immediately went to his dorm room in Baxter Hall.

As I mentioned in an earlier blog, my brothers and I got a whiff of what it was like by snooping around an army dump a week or two later and opening some cardboard canisters that once contained tear gas grenades. History is real when you can smell it.

I was a sophomore in high school then. That same year I had my mountain-top experience in faith, accepting Christ and getting baptized at Wesley Methodist Church in Jackson. The glow of young faith continued to tint every new adventure as I headed up to Ole Miss in the fall of 1965.

Rev. Jimmy Jones (not Jim Jones of Guyana) welcomed me at the Methodist Campus Ministry house on South 5th Street most Sunday evenings whenever I could attend fellowship.[5] Two friends who like me had declared physics as their major, Lois Matson and David Landskow, often joined us, but there were few other participants.

A problem, we soon learned, was that Jones worked during the week with the Delta Ministry, a church-sponsored group addressing health, economic development, and civil rights among poor (black) people in the Mississippi Delta region of northwest Mississippi.[6] It was funded by the National Council of Churches, despised as liberal agitators by most white Mississippians.[7] Rev. Jones smoked cigarettes constantly, at least partly I surmised in reaction to phone calls regularly threatening him, his wife, and two small daughters. He encouraged a few of us to experiment with our own style of worship. I never went with him on a trip to the Delta.

The following year, Earl Fyke from Jackson and other incoming freshmen at Ole Miss invited me to join them in Campus Crusade, a far more popular Sunday evening event. It felt much more familiar, required less commitment, and became my place for weekly worship.

I ran for the Campus Senate at Ole Miss and got elected along with my great friend Bill Cushman. We began to look for a dragon to slay, some noble way to strike a blow for the betterment of our campus community, and we found the perfect issue.

Haircuts. As male freshmen we had suffered the ignominy of letting upperclassmen (older brother Robert in my case) run the electric shears straight from forehead to crown and down the back side. The student government sanctioned the haircuts supposedly to heighten “school spirit.” Its true purpose, we reasoned, was to transform incoming boys into beanie-wearing goofballs, so that the attention of every new girl on campus would turn toward the upperclassmen.

Ole Miss was one of the last universities to continue the haircut ritual. Each young man paid a dollar for the cut, which went to purchase Rebel flags to wave at football games.

In the Senate debate I learned how easily a politician can lie, as I asserted agreement from university alumni that it was a backward tradition reflecting poorly on the school. In truth one alumnus, my father, said that. To bolster our case, we ferreted out a scandal. The sum collected for haircuts was less than half the number of freshman males. Either the practice was not universally applied, or someone had absconded with several hundred dollars.

The champions of tradition resisted fiercely. At least that’s how I like to remember it. The Senate just barely voted with us to eliminate the haircuts. Billy Gottschalk, the Student Body President, sat on the bill for months before finally signing it to complete the termination.

In the meantime a handful of black students continued to enroll and attend classes at Ole Miss. Our paths didn’t cross. The Methodists began a Coffeehouse ministry at the same location on South 5th Street that I attended as a freshman. I heard that blacks and whites were talking to each other there. Someone said, “You had better stay away. They’re smoking pot.” That gave me an excuse. Earl Fyke went to the Coffeehouse two or three times and felt better for it, but I never went.

When I went from Ole Miss to Harvard Medical School in 1969, I learned two things. The first was that my undergraduate education in Mississippi had given me an excellent preparation for medical school. In an early blog I wrote about how Anita Hutcherson’s sophomore honors class in ancient classics at Ole Miss was a life-changing experience.

The second thing I learned in coming to Boston was how natural it feels to spend time and become friends with African American classmates. The blog just prior to this one discusses my experience at Harvard. During a summer break, I even visited community health centers in Mississippi and met Dr. Jack Geiger in the Delta. The passion of Geiger and others for joining in community work was unforgettable. At Duke University where I have spent the past 25 years, a vigorous minority support program continues to function with gratifying success.

After 1962 the University of Mississippi suffered decades of stunted enrollment and, prominently, weakened athletic success. Slowly the University has transformed for the better.

An annual festival called Rebelee, in which the University “seceded from the Union” for a day, ceased quickly in the 1960s. The sports teams still go by the name Ole Miss Rebels, but the mascot Colonel Reb was dropped eventually in favor of a black bear. Cheerleaders used to pass out a couple thousand small Confederate battle flags at football games. That practice stopped within a decade, and the Rebel flag was banished[8] in 1997 by Chancellor Robert Khayat, a former Ole Miss football player who had black friends as playmates in childhood. In October 2015 the University took the Mississippi state flag down from the flagpole near the Lyceum, because the state flag still incorporates the Stars and Bars of the Confederacy. South Carolina has changed its state flag. Mississippi will do so also, better sooner rather than later.

Over the past decade student enrollment at the University of Mississippi has increased by 40.5% according to a recent report and currently exceeds 20,000 on the Oxford campus. The ratio of black to white students is about 1 to 6.

Today James Meredith ranks as a celebrated Ole Miss alumnus. He is the only living individual to have a bronze statue erected on the campus. Around a commemorative plaza that lies between the Lyceum and the University library, markers describe the civil rights struggle. On the south side, Meredith’s statue strides toward a portal representing equal opportunity in education and life.

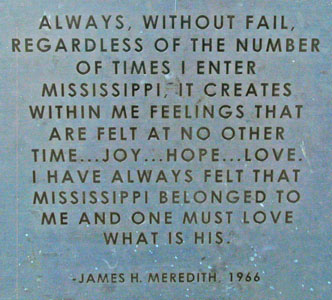

One of the markers gives this quote from Meredith:

In an earlier blog, we considered that the truest ownership derives from our choices and their consequences. In that sense James Meredith’s statement, “I have always felt that Mississippi belonged to me,” bears up undeniably. Yet unlike the claims of those who opposed him, Meredith’s right of ownership can be shared.

Next post: Reflections on Race

Previous post: Neighbors and Family

Searching for GSOT outline: Home

Images: Scenes and a plaque at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, own photos.

[1] Cohodas, Nadine. The Band Played Dixie. Simon and Schuster, New York, 1997, p. 86. Sitton, Claude, New York Times, 10/2/1962.

[2] Cohodas, p. 58.

[3] Ibid., p. 82.

[4] A federal grand jury in Mississippi later declined to indict Walker.

[5] It was 2 blocks from my early childhood home in Oxford.

[6] See Bruce Hilton’s book The Delta Ministry, Macmillan, Toronto, 1969.

[7] I learned much later that my grandfather at Yale in the 1940s chaired the planning group for the National Council of Churches.

[8] By outlawing not the flag itself, but the stick that waved it. See blog by Marilyn Tinnin here. Also Khayat, R., The Education of a Lifetime, Nautilus, Oxford, MS, 2013.